Syrups are concentrated aqueous preparations of a sugar or sugar substitute with or without flavoring agents and medicinal substances. Syrups containing flavoring agents but not medicinal substances are called nonmedicated or flavored vehicles (syrups).

These syrups are intended to serve as pleasant-tasting vehicles for medicinal substances to be added in the extemporaneous compounding of prescriptions or in the preparation of a standard formula for a medicated syrup, which is a syrup containing a therapeutic agent. Due to the inability of some children and elderly people to swallow solid dosage forms, it is fairly common today for a pharmacist to be asked to prepare an oral liquid dosage form of a medication available in the pharmacy only as tablets or capsules.

Medicated syrups are commercially prepared from the starting materials, that is, by combining each of the individual components of the syrup, such as sucrose, purified water, flavoring agents, coloring agents, the therapeutic agent, and other necessary and desirable ingredients. Naturally, medicated syrups are employed in therapeutics for the value of the medicinal agent present in the syrup.

Perhaps the most frequently found types of medications administered as medicated syrups are antitussive agents and antihistamines.

Components of Syrups

Most syrups contain the following components in addition to the purified water and any medicinal agents present:

- The sugar, usually sucrose, or sugar substitute used to provide sweetness and viscosity.

- Antimicrobial preservatives.

- Flavorants.

- colorants.

Also, many types of syrups, especially those prepared commercially, contain special solvents (including alcohol), solubilizing agents, thickeners, or stabilizers.

Sucrose and Nonsucrose Based Syrups

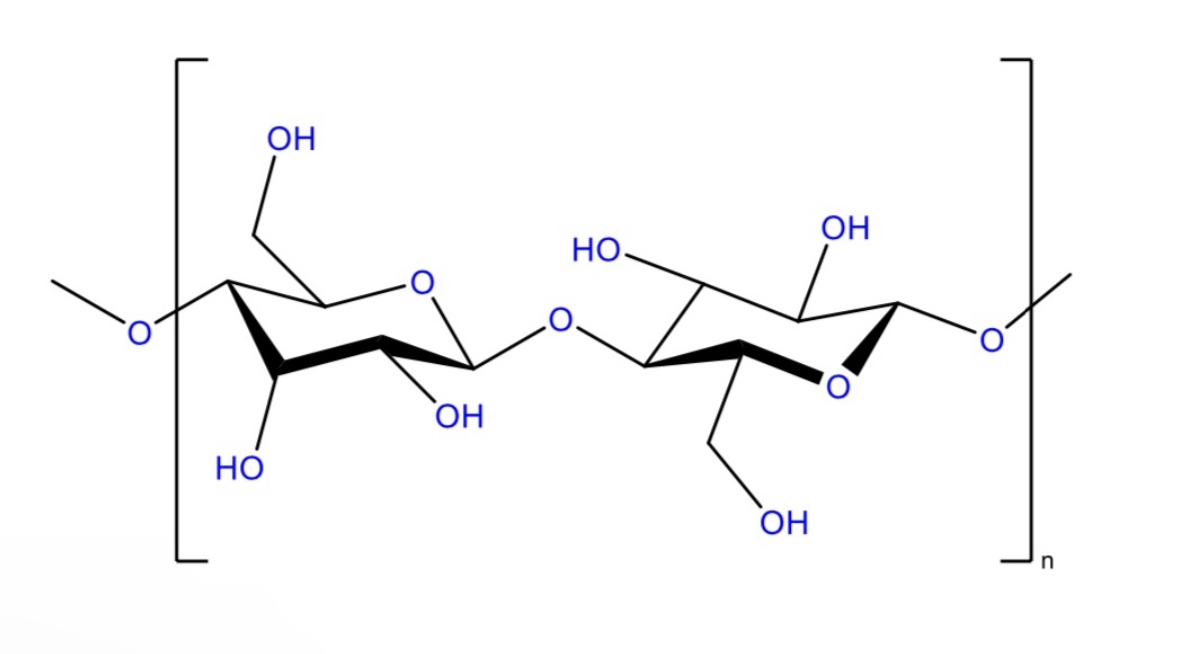

Sucrose is the sugar most frequently employed in syrups, although in special circumstances, it may be replaced in whole or in part by other sugars or substances such as sorbitol, glycerin, and propylene glycol. In some instances, all glycogenetic substances (materials converted to glucose in the body), including the agents mentioned earlier, are replaced by nonglycogenetic substances, such as methylcellulose or hydroxyethylcellulose. These two materials are not hydrolyzed and absorbed into the blood stream, and their use results in an excellent syrup-like vehicle for medications intended for use by diabetic patients and others whose diet must be controlled and restricted to nonglycogenetic substances. The viscosity resulting from the use of these cellulose derivatives is much like that of a sucrose syrup. The addition of one or more artificial sweeteners usually produces an excellent facsimile of a true syrup.

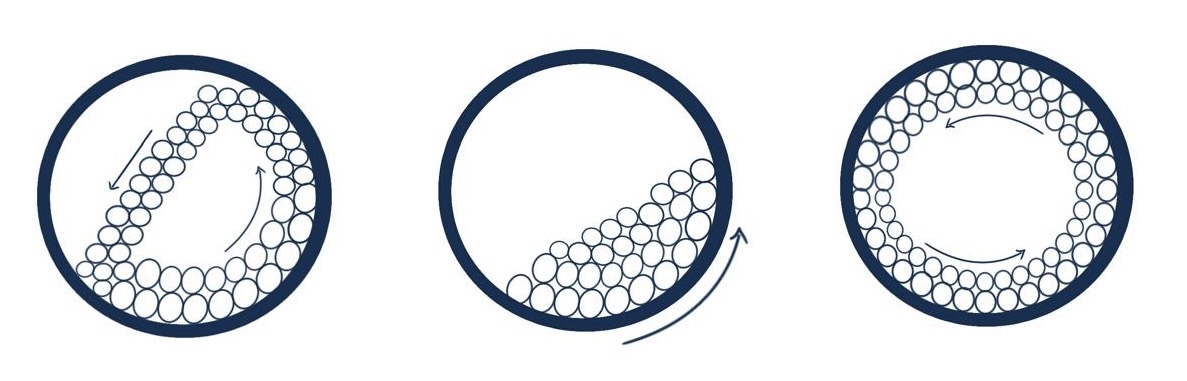

The characteristic body that the sucrose and alternative agents seek to impart to the syrup is essentially the result of attaining the proper viscosity. This quality, together with the sweetness and flavorants, results in a type of pharmaceutical preparation that masks the taste of added medicinal agents. When the syrup is swallowed, only a portion of the dissolved drug actually makes contact with the taste buds, the remainder of the drug being carried past them and down the throat in the viscous syrup. This type of physical concealment of the taste is not possible for a solution of a drug in an unthickened, mobile aqueous preparation. In the case of antitussive syrups, the thick, sweet syrup has a soothing effect on the irritated tissues of the throat as it passes over them.

Most syrups contain a high proportion of sucrose, usually 60% to 80%, not only because of the desirable sweetness and viscosity of such solutions but also because of their inherent stability in contrast to the unstable character of dilute sucrose solutions.

The aqueous sugar medium of dilute sucrose solutions is an efficient nutrient medium for the growth of microorganisms, particularly yeasts and molds. On the other hand, concentrated sugar solutions are quite resistant to microbial growth because of the unavailability of the water required for the growth of microorganisms.

This aspect of syrups is best demonstrated by the simplest of all syrups, Syrup, NF, also called simple syrup. It is prepared by dissolving 85 g of sucrose in enough purified water to make 100 mL of syrup. The resulting preparation generally requires no additional preservation if it is to be used soon; in the official syrup, preservatives are added if the syrup is to be stored. When properly prepared and maintained, the syrup is inherently stable and resistant to the growth of microorganisms. An examination of this syrup reveals its concentrated nature and the relative absence of water for microbial growth. Syrup has a specific gravity of about 1.313, which means that each 100 mL of syrup weighs 131.3 g. Because 85 g of sucrose is present, the difference between 85 and 131.3 g, or 46.3 g, represents the weight of the purified water.

Thus, 46.3 g, or mL, of purified water is used to dissolve 85 g of sucrose. The solubility of sucrose in water is 1 g in 0.5 mL of water; therefore, to dissolve 85 g of sucrose, about 42.5 mL of water would be required. Thus, only a very slight excess of water (about 3.8 mL per 100 mL of syrup) is employed in the preparation of syrup. Although not enough to be particularly amenable to the growth of microorganisms, the slight excess of water permits the syrup to remain physically stable in varying temperatures. If the syrup were completely saturated with sucrose, in cool storage, some sucrose might crystallize from solution and, by acting as nuclei, initiate a type of chain reaction that would result in separation of an amount of sucrose disproportionate to its solubility at the storage temperature. The syrup would then be very much unsaturated and probably suitable for microbial growth. As formulated, the official syrup is stable and resistant to crystallization and microbial growth. However, many of the other official syrups and a host of commercial syrups are not intended to be as nearly saturated as Syrup, NF, and therefore must employ added preservative agents to prevent microbial growth and to ensure their stability during their period of use and storage.

Antimicrobial Preservative

The amount of a preservative required to protect a syrup against microbial growth varies with the proportion of water available for growth, the nature and inherent preservative activity of some formulative materials (e.g., many flavoring oils that are inherently sterile and possess antimicrobial activity), and the capability of the preservative itself. Among the preservatives commonly used in syrups with the usually effective concentrations are benzoic acid 0.1% to 0.2%, sodium benzoate 0.1% to 0.2%, and various combinations of methylparabens, propylparabens, and butylparabens totaling about 0.1%. Frequently, alcohol is used in syrups to assist in dissolving the alcohol-soluble ingredients, but normally, it is not present in the final product in amounts that would be considered to be adequate for preservation (15% to 20%).

Flavorant

Most syrups are flavored with synthetic flavorants or with naturally occurring materials, such as volatile oils (e.g., orange oil), vanillin, and others, to render the syrup pleasant tasting. Because syrups are aqueous preparations, these flavorants must be water soluble. However, sometimes a small amount of alcohol is added to a syrup to ensure the continued solution of a poorly water-soluble flavorant. Commercial flavoring systems (FLAVORx) may also be considered and used.

Colorant

To enhance the appeal of the syrup, a coloring agent that correlates with the flavorant employed (i.e., green with mint, brown with chocolate) is used. Generally, the colorant is water soluble, nonreactive with the other syrup components, and color stable at the pH range and under the intensity of light that the syrup is likely to encounter during its shelf life.